Cataraqui

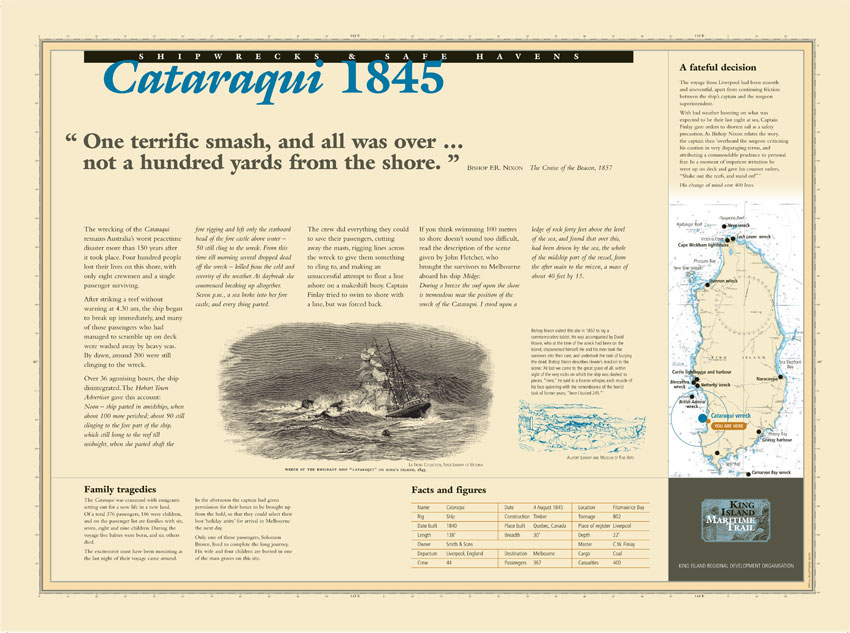

Maritime Trails: Cataraqui 1845

Australia’s worst civil disaster was that of the barque Cataraqui, wrecked on the West Coast of King Island on 4 August 1845 with the loss of 400 lives.

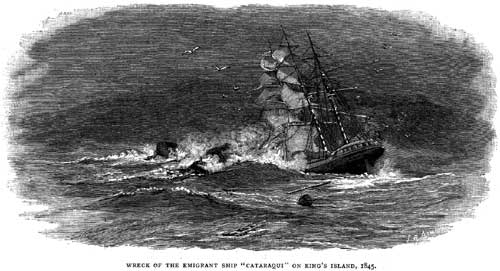

The Cataraqui sailed from Liverpool for Melbourne on 20 April 1845 with 367 assisted emigrants under the care of surgeons Charles and Edward Carpenter, and 41 crew under the command of Captain Christopher William Finlay. The passage was generally uneventful apart from the loss of one of the crew overboard, and by the time the ship aproached the Australian coastline, five babies had been born and six others had died. Consequently there were four hundred and nine persons on board when at 3 a.m. on 4 August, on getting underway again after having hove-to in a howling gale, the master calculated he was sixty or seventy miles north-west of King Island. Just 90 minutes later, the Cataraqui crashed without warning on the jagged rocks about a 150 yards offshore north of Fitzmaurice Bay and four kilometers north of the point that now bears her name, between Currie Harbour and Stokes Point. Immediately after striking there was four feet of water in the hold, and despite the ladders leading below decks being knocked away, the crew managed to get most of the emigrants on deck. It proved of little use as huge seas swept the decks and washed scores overboard, to be battered to death on the rocks by the surf. At about 5 a.m. the ship rolled onto her beam ends, and more were thorn into the raging waters. The masts were cut away to ease her, but being full of water she did not respond.

Daylight found some 200 survivors still clinging to the wreck. At about 10 a.m. the last remaining boat was launched, but immediately capsized, drowning its five or six occupants.

Sometime afterwards the hull parted amidships and the stern began to collapse, throwing perhaps 70 to 100 into the water. Around 5 a.m. the hull parted again, near the foremast, and the stern completely disintegrated, leaving perhaps 70 survivors crowded onto the forecastle. Lines were strung along what remained of the wreck to give the survivors something to cling to, and an attempt was made to drift a barrel attached to a line ashore, but it stopped 20 yards out, caught up in the kelp. By daybreak on the 5th just 30 survivors remained, and Captain Finlay made an attempt to swim ashore, but was forced back by the currents. Finally it was decided that the only chance of survival was to try to swim ashore on floating wreckage, and the lines were cut.

Chief Officer Thomas Guthrie crawled along the sprit-sail yard and was washed out to the bow-sprit, from where he reached shore clinging to two planks. Here he found an emigrant, Samuel Brown, was had come ashore at about 2 a.m. the previous night, clinging to a piece of wreckage, and a seaman who had got ashore earlier in the morning. The forecastle broke up soon afterwards, throwing the handful of remaining survivors into the water, and of them six crewmen managed to get ashore safely. They were the last to reach shore alive.

The nine castaways were lucky to be found on the following day by the “Straits Policeman,” David Howie, who had been attracted to the scene by the large amount of wreckage drifting about. He had been trapped on the island since his own boat had been wrecked there some time earlier, and the party was forced to remain there for five weeks before being rescued by the cutter Midge on 7 September and taken to Melbourne. In the meantime they buried 342 bodies that had been washed ashore in four mass graves, one holding 200.

News of the wreck caused a sensation in Melbourne, where the emigrants were headed. Several public events were organized to raise funds to assist the survivors and reward their rescuers, and an iron memorial was fabricated and erected at the scene of the wreck in 1846. It eventually rusted away, but was replaced by a stone cairn in 1956. The wreck itself was sold to builder Alexander Sutherland for 86 pounds, and a considerable amount of material was recovered, although unfortunately not enough to prevent his insolvency in June 1846. It was later sold for another six pounds, still more spars, deals, and other wreckage being salvaged. The wreck, of which no timber now remains, has been extensively dived over the years and many artifacts including cannon and anchors have been recovered.

Cataraqui was a ship of 802 tons, 138.0 x 30.0 x 22.0ft., built at Quebec in 1840 by Williams Lampson, and was registered at Liverpool in the name of William Smith & Sons.

REFERENCE: Lemon & Morgan, Pour Souls, They Perished.